My Visit to The Legacy Sites

In honor of Juneteenth, which was celebrated last week, I'd like to share my experience visiting The Legacy Sites in Montgomery, Alabama. These include The Legacy Museum and The National Memorial for Peace and Justice which opened in 2018. Additionally, I visited the newest site, the Freedom Monument Sculpture Park which opened this March.

Before delving into the details of these remarkable sites, it's important to acknowledge their origin. The Legacy Sites were established by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a nonprofit law office founded in Montgomery, Alabama by Bryan Stevenson in 1989. EJI provides legal representation to individuals who have been wrongly convicted, unfairly sentenced, or abused in state jails and prison. Inspired by his work and experiences, Stevenson created the Legacy sites to educate the public on racial injustices and honor the individual who endured slavery and its aftermath. These sites serve as powerful reminders of America’s history and provide a safe place for national healing and reflection.

<script async src="https://pagead2.googlesyndication.com/pagead/js/adsbygoogle.js?client=ca-pub-2423389887396083"

crossorigin="anonymous"></script>

The Legacy Museum:

The Legacy Museum explores the history of racial injustice in America, from enslavement to mass incarceration. As I walked through the museum, all the topics I had learned in middle and high school came rushing back: African slaves arriving in Jamestown, Virginia, the transatlantic slave trade, the Three-Fifths Compromise, the Emancipation Proclamation, and more. At that moment, I felt immense gratitude for my teachers. My education had prepared me to navigate the museum's exhibits with ease.

The Legacy Museum was not just a review of what I had learned in school; it was a deeper dive into these topics. The storytelling in the museum was particularly powerful, featuring narratives from individuals who experienced slavery. These stories included attempts to escape, searches for loved ones, accounts of wrongful incarceration, and many more. These personal stories enriched my understanding, going beyond the chronological events often presented in classrooms.

One particular exhibit, best described by the New York Times, featured “statues of chained men, women and children stick hauntingly out of sand as simulated waves crash overhead, a symbol to the estimated 2 million people for whom the slave trade ended in a watery grave in the Atlantic Ocean.” At first glance, I felt an overwhelming sense of terror. To be honest, I couldn’t believe this was an exhibit—it was raw and powerful.

Nearby, a theater played films related to the exhibit. I walked in and learned that the statues were created by Ghanaian artist Kwame Akoto-Bamfo. The exhibit in EJI is only part of his project known as The Nkyinkyim Installation, which means "Life's journey is twisted." Akoto-Bamfo plans to sculpt 11,100 figures, each representing actual people he has met. He hopes these sculptures resemble their ancestors who were enslaved, allowing future generations to see resemblances to their own family members, like mothers or uncles.

The film shared that Akoto-Bamfo's grandparents were former slaves, and many of the elders in his community in Nuhhalenya, Ada, Ghana, were as well. In the film, he nervously asks them to talk about slavery, leading to a brief pause before they break down. This pattern of hesitation among individuals who experienced slavery firsthand was recurrent throughout the museum. I found it beautiful that younger people like Akoto-Bamfo are able to share this history on behalf of those who cannot. Akoto-Bamfo claims he is “...Inspired by Ghanaian and African culture, I’m a living witness to the knowledge that is being lost to time. That is why I feel it is important to create a repository of our history and heritage in a ‘language’ using symbols that our people can relate to and understand."

I greatly appreciated the storytelling in the museum. The personal stories of those who experienced slavery enriched my knowledge. These stories are almost never told in the classroom, where events are often presented as mere chronological facts. The Legacy Museum brought these experiences to life, providing a deeper and more profound understanding of America's history of racial injustice. I wish more people could experience The Legacy Museum. Most importantly, I wished more students could learn about the deeply rooted history of slavery in our country through storytelling.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice:

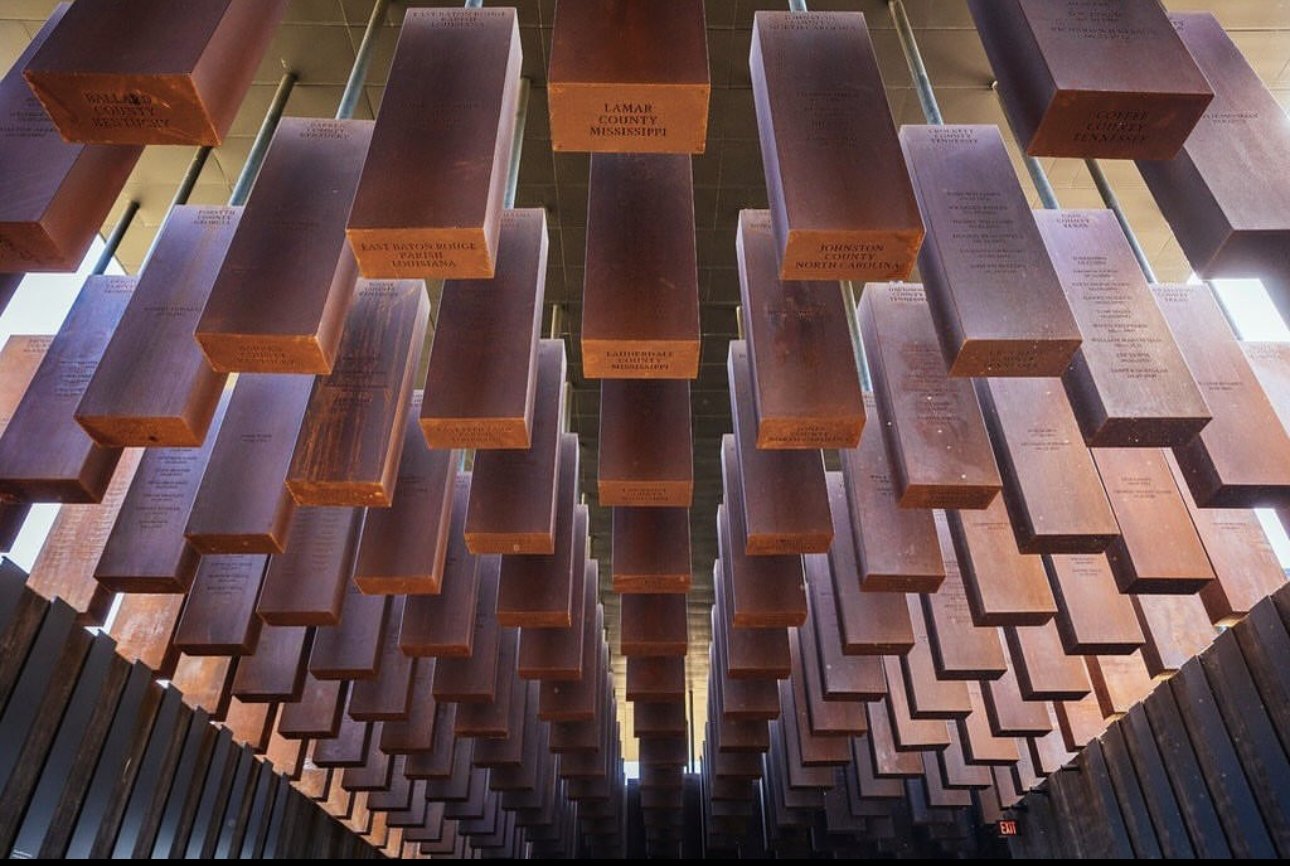

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice is the first lynching memorial in the United States. It commemorates the more than 4,000 documented racial terror lynchings that occurred across the country. The memorial's design features eight hundred Corten steel monuments, each representing a county where lynchings took place, with the names of the victims engraved on them.

I found the design of the memorial to be both clever and intentionally discomforting. At the entrance, the steel monuments are at eye level, but as I progress through the memorial, I found myself gradually looking up, mimicking the experience of looking up at those who were lynched.

As I walked through the memorial, I tried to read as many names as I could. Being from Texas, my eyes were particularly drawn to the monuments representing Texas counties. I knew that Texas had a deeply rooted history of slavery and racial violence, but seeing the sheer number of steel monuments for Texas was heartbreaking. It felt as though they would never end.

Reflecting on my experiences, I recalled the many road trips I have taken through Texas, such as drives to visit friends in College Station or going to Six Flags in San Antonio. The familiar names of places I had driven through took on a new, somber significance. I am never going to drive through Texas the same way again.

Freedom Monument Sculpture Park:

Freedom Monument Sculpture Park celebrates the achievements and struggles of African Americans throughout history. It is the third site created by the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) and aims to create a counter-narrative to the typical story encountered when learning about the history of racism and slavery in the United States. The sculptures are not only beautiful but also rich with symbolism, capturing moments of pain and triumph.

As I walked through the park, I navigated the sculptures and the first-person narratives shared through large stones. I would look at a sculpture, then turn my attention to the stones that included these personal stories. I moved back and forth like this throughout the park, absorbing the profound depictions of pain. I was particularly proud to recognize a piece by Kehinde Wiley titled "An Archeology of Silence." I had seen Wiley’s exhibit in San Francisco, where the enormous statue is displayed in the middle of a red room, making a powerful statement. The 7.5-foot-tall bronze sculpture depicts a lifeless man over a horse. The sculpture in the park, though smaller, seemed even more haunting set outdoors.

Walking through the park was challenging. The sculpture and stories vividly depicted the weight of history. These were real stories that I wished were not true. The park wasn’t simply conveying a painful narrative; it guided me through one. I remember towards the end being overwhelmed with emotion due to all the information I had absorbed.

I was able to learn that the first-person narratives concluded with stories of individuals escaping and finding freedom before seeing The National Monumental to Freedom.

As I was arriving towards the end of the park, I saw The National Monumental to Freedom. A giant wall being forty-three feet high and one hundred and fifty feet wide. There was a young man who worked for the museum standing right before entering the area. He explained that the monument is inscribed with 122,000 surnames and encouraged people to look up any names through the device provided. In that moment, my emotions were replaced with awe at the monument's enormity serving as a reminder that despite all the pain perseverance leads to freedom in the end.

Engraved in the monument there was quote that resonated with me:

Enduring the horrors and pain of slavery,

You still found the capacity to love,

to dream, to nurture a new life, and to triumph.

After my experiences at The Legacy, I gained a new perspective on slavery. Previously, I understood slavery as a series of facts and statements about the wrongdoings committed by colonizers. Leaving the museums, I had a deeper understanding of the hope and strong faith of those who endured slavery. I began to recognize that people under enslavement built communities, towns, and cities. I loved seeing families, couples, and friends walking through these exhibits, reclaiming these spaces as their own, and building an emotional connection to the hardships of slavery.

Slavery cannot be overlooked in America, yet many want to forget it. There is still an ongoing demand to remember and acknowledge these events to properly heal. Bryan Stevenson and the Equal Justice Initiative continue to fight for this remembrance. It gives me hope that others will join this effort as well to build a truthful narrative about slavery.

National Monumental of Freedom.